As of March 17, 2020, the World Health Organization has estimated that 179,111 people worldwide have been infected with the coronavirus, including 91,779 in the Western Pacific (51.2% of total), 64,188 in Europe (35.8% of total) and 4,910 in the Americas (2.7% of total). Deaths worldwide are estimated at 7,426 (4.1% of those infected). I emphasize “estimated”, since many cases of the virus have mild symptoms and do not end up being captured in the data.

The virus has almost certainly sent the global economy into recession, shuttering airports, hotels and restaurants and closing the US-Canada border to non-essential travel. In the midst of this public health challenge, quite understandably, not many people are thinking about the long term. Yet recognizing that “this too shall pass”, we wanted to share some lessons about long-term investing that charities can learn from current events.

High-quality bonds

We have been emphasizing the importance of high-quality, short- to mid-term bonds for quite a while. This is what protects the portfolio in tough times and ultimately allows charities to take measured risks where they are more likely to be rewarded – with stocks. There are serious risks in “reaching for yield” with bond substitutes. Below we compare the year-to-date performance of high-quality bonds and low-quality bonds (fund total returns at market price, as at March 17, 2020):

Canadian short-term federal bonds (ZFS): 2.8%

Canadian short-term bonds (VSB): -1.6%

Canadian low-rated corporate bonds (HYB): -14.8%

Canadian preferred shares (ZPR): -31.0%

The performance of bond substitutes, in Warren Buffett’s phrase, shows who has been swimming without their shorts. Canadian stocks have returned -25.1% year-to-date. Imagine if a charity were unlucky enough to hold a portfolio of 50% Canadian stocks and 50% preferred shares. Their year-to-date return would be about -28%. Try starting the year with $1 million and losing $280,000 within a matter of months, when you thought you were playing it safe. Quite a rude awakening!

Global stocks

Canadian charities, just as much as other Canadian investors, have a pronounced “home bias” in their investments. This means that they invest far more in Canadian securities than they should. This home bias is prompted by a number of impulses, including that Canadian companies seem more familiar, Canadian investments are made within a democratic country governed by the rule of law, a need to maintain liquidity in Canadian dollars to meet regular expenses and a desire to support Canadian companies. Below we compare the year-to-date performance of Canadian, US and international stocks (the last two are currency-unhedged, with exposure to the movement of foreign currencies):

US stocks (ZSP): -14.3%

International developed stocks (ZEA): -21.3%

Canadian stocks (XIC): -25.1%

Safe and familiar Canadian stocks have exhibited the lowest return and high volatility, with Canada’s export-oriented economy pummeled by the coronavirus and the oil price.

US dollar

This leads us to the question of currency exposure. A significant part of the stronger performance of US stocks is because of the role of the US dollar. During extreme events like the dot-com crash of 2000-01, the global financial crisis of 2008-09 and the coronavirus, large global investors like insurance companies and pension funds move parts of their portfolios from stocks to bonds, seeking the safety of US Treasury bonds and the staying power of the global reserve currency. In 2001 and 2002, the US dollar rose 3.7% and 5.9% respectively against the Canadian dollar. In 2008, the gain was a more dramatic 22.2%. In 2020 year-to-date, the US dollar has surged 9.1% against the Canadian dollar and could see further gains as the impact of the coronavirus extends over the spring and summer. The point here is similar to foreign stocks. Although it seems more risky to have exposure to foreign currencies, this often helps Canadian investors reduce risk during stock market downturns. The Canadian dollar is highly exposed to the global trade cycle, while the US dollar benefits from the flight to safety of global investors. The currency decision makes a difference. Safe and familiar Canadian stocks lost 25.1%, while bad old US stocks lost 14.3%. A big part of this difference was the US dollar.

Asset mix

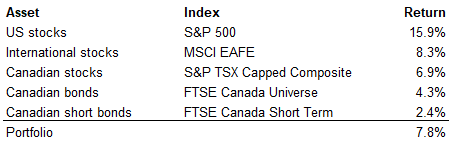

The above points apply to charities who are investing, which we would define as at least 40% of the portfolio in stocks. Yet the most important point we make today is for charities who are either not investing, or barely investing with 20-30% of the portfolio in stocks. Over the last decade, a typical charity’s portfolio earned 3% annualized, while a benchmark 60/40 portfolio earned 7.8% annualized (see previous post). Let’s say a charity invested $1 million at the start of 2010 and held to the end of 2019, assuming no contributions or withdrawals. With the 3% annualized return of a typical portfolio, the ending balance would be $1.3 million. With the 7.8% annualized return of a benchmark portfolio, the ending balance would be $2.1 million. The higher return of the benchmark portfolio was worth an extra $800,000, for each $1 million invested. This is not free money. It has to be earned, by having generous donors and funders, by having engaged board members, by considering how the funds will support the organization’s long-term objectives, by developing a careful Investment Policy Statement and by investing patiently for the long term. The process is not meant to be easy, since it involves sticking to a plan during periods of considerable uncertainty. The key point from this post is that charities who are currently holding most of their long-term funds in cash or GICs should not be too quick to congratulate themselves. Certainly, they have been insulated from the extreme volatility of this year’s markets. But they have also been insulated from the 7.8% annualized growth of a benchmark portfolio over the last decade. Even with all the challenges of 2020, charities should not forget about long-term objectives. Where do they want to be in 2030? Do they have the right investments to help them get there?