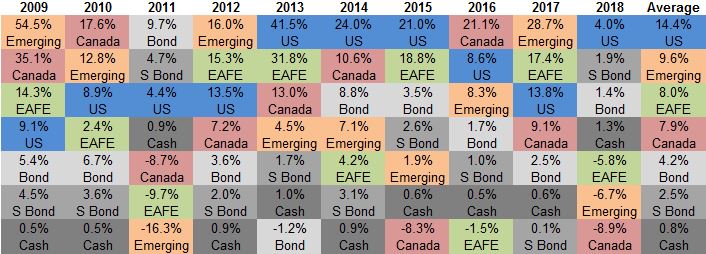

Last year ended in dramatic fashion, with the worst December for US stocks since 1931. This can prompt savers to become more attached to cash for safety and investors to question their approach to holding stocks and bonds. When it comes to the principles of how investment risk is rewarded, however, we suggest that 2018 was more about continuity than change. To explore this idea, let’s review the returns of the major asset classes, for the 10 years ending 2018:

US: S&P 500

Emerging: MSCI Emerging Markets

EAFE: MSCI EAFE (Europe, Australasia and Far East)

Canada: S&P TSX Capped Composite

Bond: Canadian bonds

S Bond: Canadian short-term bonds

Cash: Canadian three-month Treasury bills

Change

While 2018 ended with a wild ride, the annual results were quite tame. A benchmark portfolio of 60% global stocks and 40% Canadian bonds was down about 3.6% for the year. This is a small loss by almost any standard and perhaps only seems like a surprise when compared with the fruits of a long bull market, when the same benchmark portfolio returned 10.6% annualized in the 10-year period from 2009 to 2018.

Continuity

The last decade happens to have borne out several long-term trends in financial markets.

- Stocks beat bonds. While stock returns ranged from 14.4% for the United States to 7.9% for Canada, stocks handily beat bonds.

- Bonds beat cash. Bond returns ranged from 4.2% for all bonds to 2.5% for short-term bonds, both much higher than cash.

- Cash is less safe than it looks. Cash only returned 0.8%, losing purchasing power to inflation at 1.6%. In 2011 and 2018, the two worst years for stocks, cash was beaten by bonds.

Implications

Asset mix is the most important decision for long-term investors. If foundations and charities are investing for the long term, then they should consider a healthy allocation to stocks, mixed appropriately with high-quality bonds. For the many institutions that are not investing but instead saving, cash can significantly reduce long-term returns. Imagine a school or hospital had raised $10 million at the start of 2009, as part of the funding to build a new sports centre or cardiac unit. Over the next 10 years, a saver’s portfolio split between short-term bonds and cash returned 1.7%, while an investor’s portfolio, as outlined above, returned 10.6%. Hypothetically, the saver would have ended up with $11.8 million, while the investor would have ended up with $27.4 million (not adjusted for inflation, fees or costs). This is certainly not a typical case, as returns were unusually strong over the last decade. Yet in this case, deciding to invest rather than save was worth more than $15 million, enough to make a big difference to students, patients or other members of the community. Consider your long-term objectives and decide whether saving or investing is better for the community you serve.